Lejla Čehajić

LEJLA ČEHAJIĆ was born in 1978 in Sarajevo. She graduated from the High School of Applied Arts in Sarajevo, at the Department of Sculpture. In 2004 she graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Sarajevo, at the Department of Sculpture in the class of professor Mustafa Skopljak. At the same Academy, she completed her postgraduate studies, at the sculpture department, on the topic "Sculpture through the play of artistic and expressive elements of theatre and puppet theatre".Since 2005 she has been the member of Fine Artists Association of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the period 2010 to 2014, she was a member of the Art Council of ULUBiH. She exhibited in about 50 collective and 7 solo exhibitions. She also participated in several art / sculpture colonies.

She won several awards for her artistic work, including: the Kenan Solaković Sculpture Award, the Grand Prix at the ULUBiH Exhibition on April 6, the International "Private and Public" Award in Mostar and many others.She is the creator and performer of puppets for the puppet show "Zečić Uplašić" at the Sarajevo Youth Theater.She lives and works in Sarajevo as a professor at the High School of Applied Arts, Department of Sculpture.

Contact email: lelacehajic@hotmail.com

www.lejlacehajic.art

"In our hectic and insensitive lives, there are surprisingly few hours in which the soul can be self-aware, in which life gives way to meaning and spirit, (...) but this is always accompanied by discomfort and torture." Herman Hesse

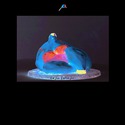

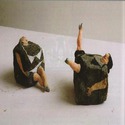

The art of idlenessAcademic sculptor Lejla Ćehajić began the cycle of Minderpuza sculptures with the idea of presenting the "pleasure of idleness", moments of complete relaxation of body and mind, that is, absolute laziness. The sculptures are painted, small in size (up to 40 cm) and made of plaster, granite, clay or a combination of these materials.

At the same time inspired by Herman Hesse's text, The Art of Idleness and the unwritten philosophy of the Bosnian ceif, Minderpuzes are sculptures of the female body presented in the intimacy of self-sacrifice, that is, in a time a woman dedicates to herself, her body. However, it should be kept in mind that the "commitment to the body" of a minderpuza is not limited to physical, but on the contrary, that physicality transcends the physical. These sculptures, in fact, repeatedly point to the sphere of the mind and the state of mind. The female body here is only an element to achieve the transcendent, that element needed for the achievement of one true minderpuza. Therefore, it should be understood: minderpuza is not a quality of character, but a state which the spirit is capable of achieving. The female body of sculpture and the linguistic gender feature, that is, the female connotation of the name minderpuza, in Lejla Ćehajić's cycle, should be understood as an element for achieving the goal, and not the goal itself. The artist's verbalized attitude is that these sculptures should by no means be interpreted as a feminist statement. These are not representations of a woman at the toilette, objects unconscious of gaze, observed, like Edgar Degas models, "through the keyhole." Nor are, for different interpretations, open representations of women in moments after hard, unrecognized, female work and eternal, pathetic anticipation, romantic heroines of literature like, maybe, Marianne by the pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais, who because the picture stretches and grabs a painful cross, in criticism, throughout history, has often been accused of peomiscuous thoughts and all sorts of erotic provocations. The cycle of Minderpuza sculptures, having all the above in mind, should be interpreted outside the notion of the physically feminine, but not entirely without it. The sculptures of this cycle, however, undoubtedly represent emphatically female bodies and this feature does not allow to bypass or ignore the element of femininity in the notion of minderpuza. The initial concept of the cycle, a depiction of universal human leisure, presented in a female body uninterested for the observer, which neglects and transcends the observer, enjoys itself, and as such represents a parallel, a counterpart to the masculine principle, a depiction of absolute activity which it evokes in its femininity, according the circumstances has been expanded and modified.

The sculptures of this cycle originally, through the elements of the female principle, passive-aggressive attitude, absolute acceptance of its own being, had to present the universal - complete reconciliation with what it is.

"In our hectic and insensitive lives, there are surprisingly few hours in which the soul can be self-aware, in which life gives way to meaning and spirit, (...) but this is always accompanied by discomfort and torture." Herman Hesse

The art of idlenessAcademic sculptor Lejla Ćehajić began the cycle of Minderpuza sculptures with the idea of presenting the "pleasure of idleness", moments of complete relaxation of body and mind, that is, absolute laziness. The sculptures are painted, small in size (up to 40 cm) and made of plaster, granite, clay or a combination of these materials.

At the same time inspired by Herman Hesse's text, The Art of Idleness and the unwritten philosophy of the Bosnian ceif, Minderpuzes are sculptures of the female body presented in the intimacy of self-sacrifice, that is, in a time a woman dedicates to herself, her body. However, it should be kept in mind that the "commitment to the body" of a minderpuza is not limited to physical, but on the contrary, that physicality transcends the physical. These sculptures, in fact, repeatedly point to the sphere of the mind and the state of mind. The female body here is only an element to achieve the transcendent, that element needed for the achievement of one true minderpuza. Therefore, it should be understood: minderpuza is not a quality of character, but a state which the spirit is capable of achieving. The female body of sculpture and the linguistic gender feature, that is, the female connotation of the name minderpuza, in Lejla Ćehajić's cycle, should be understood as an element for achieving the goal, and not the goal itself. The artist's verbalized attitude is that these sculptures should by no means be interpreted as a feminist statement. These are not representations of a woman at the toilette, objects unconscious of gaze, observed, like Edgar Degas models, "through the keyhole." Nor are, for different interpretations, open representations of women in moments after hard, unrecognized, female work and eternal, pathetic anticipation, romantic heroines of literature like, maybe, Marianne by the pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais, who because the picture stretches and grabs a painful cross, in criticism, throughout history, has often been accused of peomiscuous thoughts and all sorts of erotic provocations. The cycle of Minderpuza sculptures, having all the above in mind, should be interpreted outside the notion of the physically feminine, but not entirely without it. The sculptures of this cycle, however, undoubtedly represent emphatically female bodies and this feature does not allow to bypass or ignore the element of femininity in the notion of minderpuza. The initial concept of the cycle, a depiction of universal human leisure, presented in a female body uninterested for the observer, which neglects and transcends the observer, enjoys itself, and as such represents a parallel, a counterpart to the masculine principle, a depiction of absolute activity which it evokes in its femininity, according the circumstances has been expanded and modified.

The sculptures of this cycle originally, through the elements of the female principle, passive-aggressive attitude, absolute acceptance of its own being, had to present the universal - complete reconciliation with what it is.

Dijana Čustović